HANS STOISSER

Is Covid sparing Africa?

Bill Gates and others warned of 10 million Covid deaths, ailing health systems, mass death. Such images of Covid-19 in Africa were all over our media in January and February. Now in December, in the same media, we wonder why this catastrophe failed to materialise. – An assessment.

Diesen Artikel auf Deutsch hier lesen

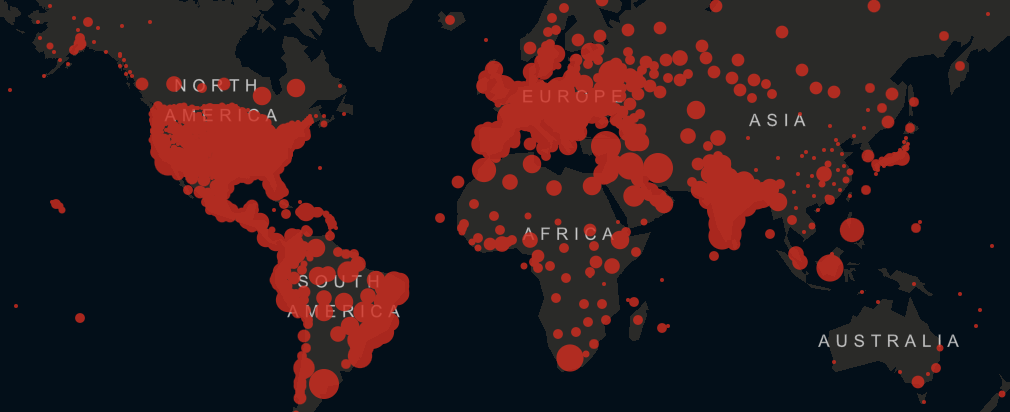

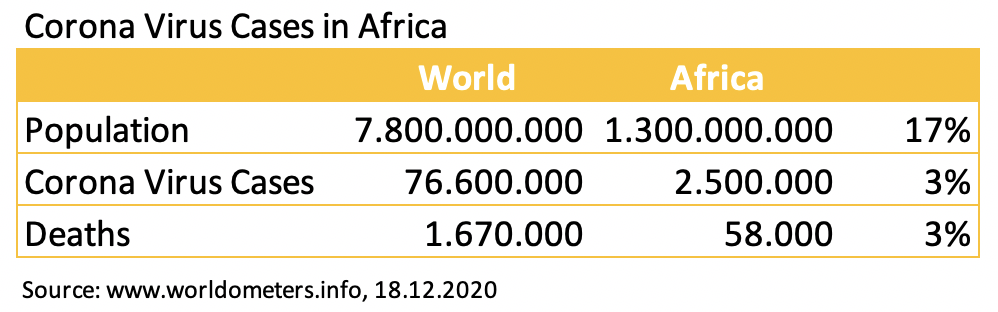

First, the facts. On the African continent, nearly 2.5 million Covid-infected people were reported as of 18 December, of whom about 58,000 have died. With Africa accounting for 17% of the world’s population, only 3% of Covid infections and deaths occur.

Instead of millions of people, “only” 58,000 have died so far. Instead of a disproportionate number of deaths, the mortality rate on the African continent is 5.5 times lower than the average for the rest of the world. – How can it be that the pandemic in Africa is not only not worse, but even far less rampant than in the rest of the world? And will it stay that way?

Underestimated health systems

The most significant blind spot of the Western world was its assessment of African health systems. This was firstly prejudiced because we do not trust African countries to have functioning systems. In fact, Senegal, Rwanda, Ethiopia, Kenya and many other African countries have recent experience with epidemics. They have used this and reacted much more quickly than we have: rapid lockdowns and quick arrangements of health facilities. Many of the decentralised outposts are not highly technical. But in the area of basic hygiene and health care, they are very often in an effective exchange with the population.

Secondly, our assessment was simply wrong. Our reporting had focused on the small number of ventilators and intensive care beds – for example: “150 intensive care beds for 105 million people in Ethiopia” – and disregarded the basic care provided by the health system. Intensive care beds, however, can only ever help a few people with little chance of success; well-functioning basic care, however, can help hundreds of millions of people to cope with the virus.

Thirdly, we have underestimated the innovative power of African countries. Scientists in Senegal developed a $1 Covid test kit at a very early stage. Ghana built a contact tracing system with community volunteers using innovative “pool testing”. Multiple blood samples are tested together, only followed up as individual tests if positive. Rwanda uses robots to measure temperature and drones equipped with megaphones to inform rural populations. In addition, technicians in Kenya and Rwanda had succeeded in building functional respirators in just a few weeks.

Young population and higher number of unreported cases

With their young populations, African countries have a serious advantage in coping with the pandemic, as the severity of the disease and mortality rates are disproportionately higher in older patients.

The median age of the population is less than 20 years in African countries and more than 40 years in European countries. In Africa, only just under 3% of the population is older than 65 years, in Europe it is almost 20%. Initial analyses based on age-related mortality rates have shown that due to the younger age, a mortality rate two to five times lower is to be expected. The much younger population would thus explain a large part of the current low mortality rate.

The number of Covid tests performed per million population is much lower in African countries than in ours. This leads to the assumption that the number of unreported cases of registered Covid infections is higher in African countries.

Thus, a plausible hypothesis is: African countries have a higher number of unreported infections, but not so much of unreported deaths. These are actually much lower than in our countries.

Immunities and climatic conditions

However, the greater epidemic experience, the younger population and the higher number of unreported cases do not fully explain the better performance of African countries. At least that is what many analysts think.

Some evidence seems to suggest that a larger number of people in Africa have built up effective immunities. According to WHO statistics, more than half of all people in Africa still die of infectious diseases such as malaria or tuberculosis. This means that, on average, people are exposed to and treated for infectious diseases at a much higher rate. This could have built up “cross-immunities” to a greater extent. For example, a study pointing in this direction attributed a reduced mortality rate in Covid-19 patients to the tuberculosis vaccination, which is widespread in Africa.

In addition, there are different climatic conditions. North Africa and South Africa with partly Mediterranean climates have much higher infection rates; countries with tropical or subtropical climates much lower. According to our epidemiologists, the cool temperatures favour the spread of the pandemic.

My colleague and Africa expert Thomas Kukovec refers to the well-known Italian immunologist Vittorio Colizzi. He says that in many African countries the climatic conditions make it difficult for secondary infections to spread. Many people are infected with the virus, but infections of the lungs or other organs do not take place.

Conclusions

African countries are suffering a massive economic crisis in the wake of the measures taken to combat the pandemic. However, the Africa health catastrophe that was widely heralded in the media has failed to materialise. African countries have mastered the health crisis comparatively well so far, thanks to functioning institutions and the competence of their staff.

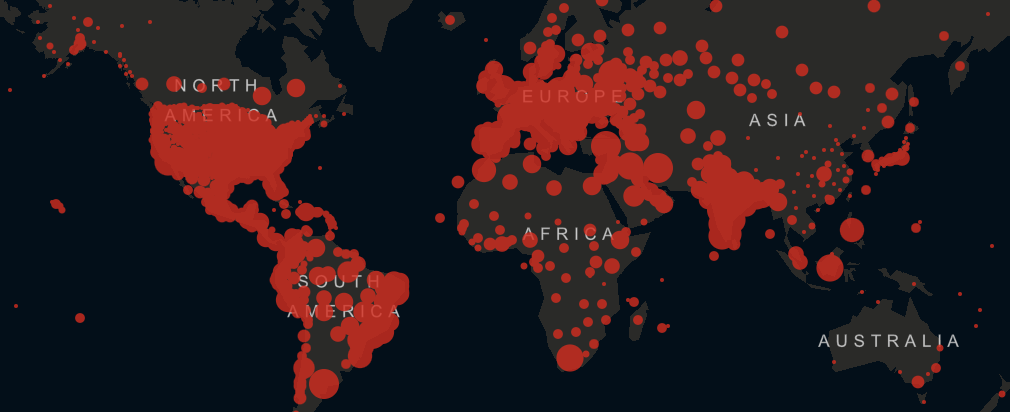

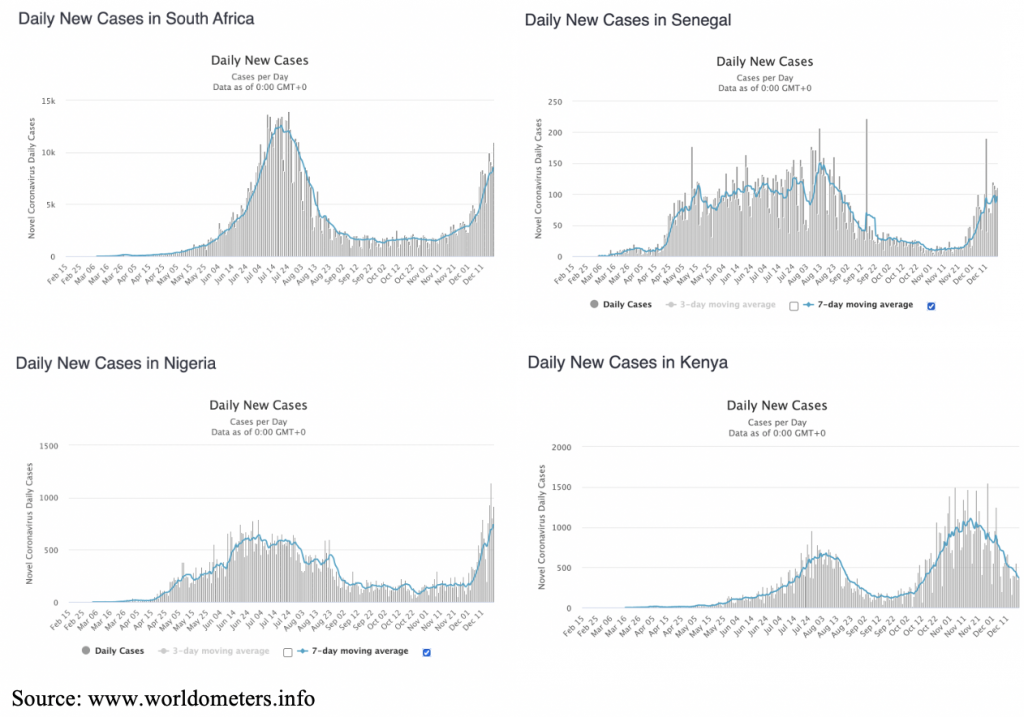

But the health crisis is not over yet. Large area countries such as Congo, Angola or Niger have a much smaller transport network in rural areas. This suggests that a spread of the pandemic is still to come. And in countries like South Africa, Nigeria or Senegal, a second wave of infections is just building up. In Kenya, they are in the process of overcoming it.

We should avoid switching from the announcement of the health catastrophe to the opposite – the miracle of sparing Africa from the pandemic. This will not happen. Despite the youth and robustness of the population, African health services have hard work ahead to further combat the pandemic.